In Retrospect OF FATHER AND SON –

STEINBECK IN THE VIETNAM WAR

Picture 1: The 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to John Steinbeck for his lifetime works. He is the 6th American Nobel Prize laureate while the 5th goes to Ernest Hemingway in 1954.

[ photo from the Nobel Foundation archive ]

JOHN STEINBECK, 1962 NOBEL PRIZE LAUREATE

Born on 02/27/1902 in Salinas, Central California. He grew up in the lush rural valley called the “Salad Bowl” watered by the Salinas River. After graduating from high school (1919), he had his heart set on becoming a writer and took courses in English literature and Creative writings at the well-known Stanford University near Palo Alto. In 1923, Steinbeck signed up for Biology courses at Hopkins Marine Station where he met Williams E. Ritter and became more interested in Ecology. In 1925, after 6 years, he left Stanford without a degree on account of his infrequent attendance record. Steinbeck decided to move to New York taking on all kinds of menial jobs to live and try his luck in journalism and writing but failed to have his first book published.

Three years later (1928), Steinbeck returned to California. He worked at anything that came his way, including as a tour guide at Lake Tahoe, but was financially struggling. He then moved to a small cottage owned by his father on the Monterey Peninsula. With the free rent and financial assistance from his older brother, Steinbeck could devote himself to the pursuit of writing without having to look for work. However, things got worse in the midst of the Great Depression. Steinbeck bought a small boat and tried to earn a living by fishing in the coastal area. When he found out that the fish and crabs he caught and the vegetable he grew in his garden could not meet all their living expenses, he and his wife were forced to apply for welfare benefits.

Steinbeck persisted in his writing but was unable to make a name for himself. Not until 7 years later (1935) when his book Tortilla Flat brought him some recognition. The novel is set in Monterey, California where he lived, during the post-World War I years. It portrays large groups of poor paisanos leading a dissolute life marked by drinking, lust, and even petty theft. They were victims of historical circumstances. Tortilla Flat was well received by critics and brought him financial success.

Two years later, his book Of Mice and Men (1937) was published. It relates the tragedy of two itinerant paisanos sharing the common dream of buying their own ranch. No matter how hard they tried, they were doomed to the harsh life of migrant agricultural laborers. George Milton was small in stature but cunning while Lennie Small, contrary to his last name, was a giant brute. His violent and erratic temperament makes him dependent on George to deal with the challenges of everyday life. The book is only a little over 100 pages long but was cited by the 1962 Committee of the Nobel Prize in Literature as “a little masterpiece”.

Next came The Grapes of Wrath (1939). It is the story of the Joads, sharecroppers in Oklahoma, who lost their property due to the dust storm during the Dust Bowl and moved to California, the land of “milk and honey”, in search of better living. Unfortunately, they met with countless difficulties, scarcity of work, low wages and hardships. Steinbeck wrote the book using plain spoken language, rich with imageries exposing the greediness of wealthy landowners and the resulting social injustices. That judgmental stance made him an undesirable figure at home. A research group at Stanford University, recently considered Steinbeck as a writer of the environment.[9]

In 1940, The Grapes of Wrath brought Steinbeck the National Book Award as well as the prestigious Pulitzer Prize in 1962. This book has been continuously republished over the years.

Both Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath were written during the Great Depression of the 1930s. They are regarded among the top in American literature and John Steinbeck’s best works. Both were made into films. Henry Fonda played Tom Joad in the Grapes of Wrath and was nominated for a best actor Academy Award.

Though The Grapes of Wrath brought Steinbeck fame and success but, on the other hand, it also generated hostility to him on account of its socialist extremism – Steinbeck was suspected of harboring communist leanings because of his strong defense of the poor working class being exploited by the rich, powerful capitalist owners of the lion’s share of the land and farms in alliance with the financier bankers.The Grapes of Wrath, first published in April, 1939, became an instant best seller in the U.S. but in his home turf it was accused of being “obscene, misrepresenting the truth” with its negative portraying of the migrant workers’ life in California.

The book suffered public burning twice in Salinas. During one of the public burnings in Bakersfield, the rich owner of cotton and potato farms, head of the local Associated Farmers W.B. “Camp” declared: “We are angry, not because we were attacked, but because we were attacked by a book that is obscene in the extreme sense of the word.”

Nevertheless, there were people who were brave enough like Gretchen Knief, librarian of Kern County, who at the risk of losing her job warned: “If that book is banned today, what will be banned tomorrow? It’s such a vicious and dangerous thing to begin.”

The Grapes of Wrath was banned by Kern County Board at schools and libraries in 1939. The ban was lifted two years later in 1941.

During the Second World War, Steinbeck worked as a war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune (1943). He accompanied the shock troops during the landing of Italy to fight Germans on the islands in the Mediterranean Sea. Wounded, Steinbeck went back home suffering from trauma. He overcame the challenge by writing.

In 1947, Steinbeck was among the few Americans allowed to visit the Soviet Union after the Communist Revolution. Going along with him was the photojournalist Robert Capa. His book A Russian Journal was published the following year (1948) with the photographs taken by Capa. The Communist government at the time considered Steinbeck an “American progressive writer” in the leftist socialist sense.

In the same year, Steinbeck was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

In 1952, the long novel East of Eden went into publication. Steinbeck considers it his magnum opus. It was later made into a film (1955) with James Dean, a well-known talented young star, playing Cal Trask.

In 1961, Steinbeck published The Winter of Our Discontent, dealing with the moral decline in the U.S.. It was not favorably received by critics.

In 1962, to his own astonishment Steinbeck was chosen for the Nobel Prize in Literature for his works and “for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception”. His characters were all victims of history, of the depression. His selection for a Nobel Prize was harshly criticized by the Swedish press and even in the U.S.. Nevertheless, in the following years Steinbeck was acclaimed as “a giant of American letters”. A number of his works was accepted as classics of Western Literature.

It is ironic that in spite of being a Nobel Prize laureate, according to the American Library Association, Steinbeck is among the 10 authors whose writings were banned. From 1990 to 2004, Of Mice and Men ranked 6 in the 100 books being banned in the United States.

In 1964, Steinbeck was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by his friend President Johnson. He occasionally served as the President’s speech writer.

STEINBECK – OF FATHER AND SON IN THE VIETNAM WAR

John Steinbeck has two sons with his second wife Gwyndolyn Conger. Thomas Myles Steinbeck, the oldest, was born in 1944 and his younger brother John Ernst Steinbeck IV in 1946. During the Vietnam War, both of his sons who were of military age were drafted.

When John IV, the second son, completed his basic training; Steinbeck proudly took him to see and shake hand with President Lyndon B. Johnson in the Oval Office at the White House. John IV went to Vietnam and served as a war correspondent for the US Military Radio and TV networks in Pleiku. His oldest son Thomas Myles Steinbeck was also drafted and stationed at Fort Ord, California. He may also run the risk of being shipped to Vietnam.

At the time the American government decided to send waves upon waves of troops to fight in Vietnam (1965), Steinbeck, though already 64 and past his prime, embarked on a 5-month trip to visit Southeast Asia. Having worked as a war correspondent during World War II, he was no stranger to military conflicts. This time around, he again worked for the paper Newsday, Long Island New York as a war correspondent. John Steinbeck traveled all over South Vietnam for six weeks, [ from 12.1966 to the start of 1967 ].

*

*

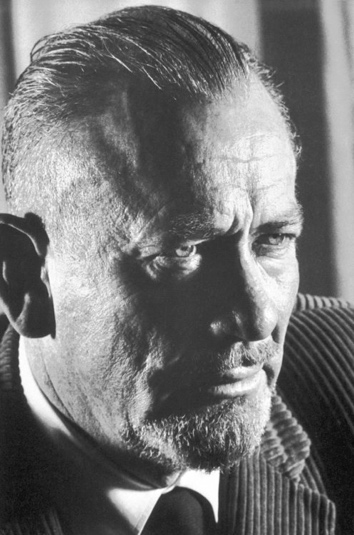

Picture 2: left,John E. Steinbeck and his 19 year-old son John IV 19 met and shook hand with President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Oval Office, White House on Monday 05/16/1966 before going to Vietnam. Steinbeck is a friend of President Johnson since 1963. The meeting lasted for 4 minutes on Steinbeck’s request. [source: LBJ Library and Museum]; right: John IV in Vietnam in 1966. The three have joined the ranks of the “departed” a long time ago.

For a long time, Steinbeck showed his contempt of the anti-war protestors. He looked at them as spineless when compared to the American soldiers serving in Vietnam. He not only condemned them but also entertained the idea of dropping them along the Ho Chi Minh trail to see how they can survive.

His literary reputation, Nobel Prize laureate and friendship with President Johnson, assured Steinbeck of special treatments. He moved around on a personal plane in the company of top military commanders including General William Westmoreland. He was constantly briefed with a rosy picture of the war situation that led him to believe in an eventual American victory.

He usually spent the daytime at the battlefields. If not too far from Saigon or not required to stay overnight at the front, Steinbeck would go back to the Caravelle Hotel for the evening, eat dinner at the plush restaurant on the 9th floor, from where he could see flares as well as hear the distant explosions of artillery shells. It was from here that Steinbeck wrote his Letters to Alicia. [Alicia Patterson – was the wife of Harry Guggenheim, co-founder of the paper Newsday. She was a Pulitzer winner reporter who passed away 3 years prior to the time Steinbeck wrote Letters to Alicia].

Upon his arrival in Vietnam, Steinbeck was fascinated with the modern weapons used by the American troops. He did not encounter anything like that during World War II. Like when he watched, for the first time, an AC-47 / “Puff the Magic Dragon” equipped with machine guns possessing such extraordinary firepower that, in a matter of seconds, they could totally cover a large football field with their 50-mm bullets. Steinbeck became so subjective when he observed, “With such modern weapons, how could the U.S. loose the war to such backward enemy.”

Steinbeck also went to a shooting range to test fire a M-16. A fact that escaped Steinbeck’s attention was, unlike the AK used by the VC, the American M-16 tended to jam in action and created a deadly scandal that was never mentioned by Steinbeck in the reports he sent from Vietnam to the paper Newsday.

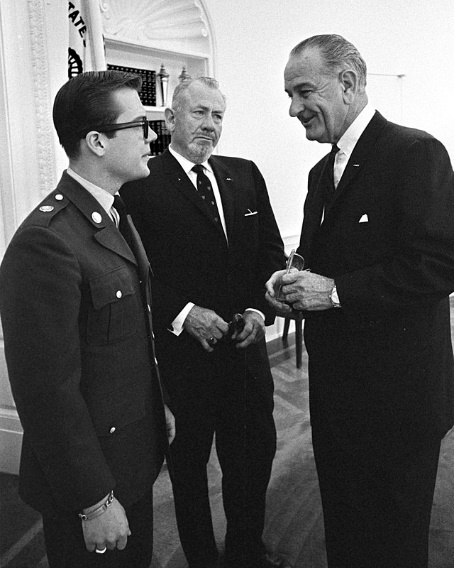

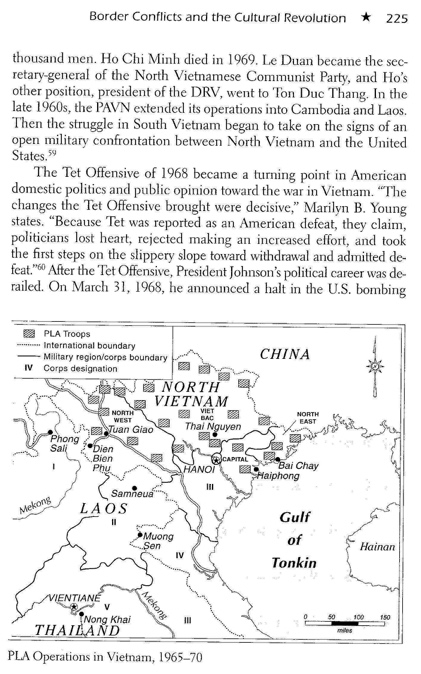

With only 6 weeks spent in the battlefields and constantly under good protection, it would be difficult for John Steinbeck to realize that: the Communist North Vietnamese troops were equipped with the most up to date armaments manufactured by the Soviet Union and Communist China. Furthermore, in North Vietnam, several divisions of Chinese volunteers disguised as North Vietnamese soldiers were manning antiaircraft missile launchers ready to shoot down the F105 Thunderchiefs of the Seventh Fleet flying in to bomb North Vietnam. [6]

Such an important fact was kept out of the most recent official history books published by Hanoi. No mention was made that in order to deal with the American and South Vietnamese forces, during the period of 1965 to 1970, on the request from Ho Chi Minh, Mao Tse-tung dispatched 320,000 soldiers of the Red Army to North Vietnam. In 1968, he sent an additional 110,000 troops to Laos (total: 430,000). Those divisions of “volunteers” either took cover in the numerous caves in Lạng Sơn, Hà Nam or hid in isolated jungles. They kept their presence under wraps and were not allowed to get in contact with the local population. [6B]

Picture 3: left, The Dragon in the Jungle: The Chinese Army in the Vietnam War. Xiaobing Li. Oxford University Press, Jan 30, 2020. [6A]; center: map showing the PLA troops locations in North Vietnam and Laos during the Vietnam War 1965-1970. [6B]

right, Book cover of Lịch Sử Việt Nam Volume 13 (for the period from 1965 to 1975) published in 2017 by the Viện Sử Học, Viện Hàn Lâm Khoa Học Xã Hội Việt Nam, no reference was made of this important historical fact in the pages 125 -126. A truthful, complete history of Vietnam needs to be rewritten by the clear minded Second Generation of Vietnamese. [private source: Từ Mai Trần Huy Bích] (B)

Many details about that “ghost army” were mentioned in the book “The Dragon in the Jungle, The Chinese Army in the Vietnam War” by Xiaobing Li published by Oxford University Press 2020. [4] To this day (2021), in the caves in the forests and mountains of North Vietnam, we can still see slogans in Chinese written on the rock walls: Long live the Sino-Vietnamese friendship, Long live Chairman Ho, Down with American Imperialism. [8]…

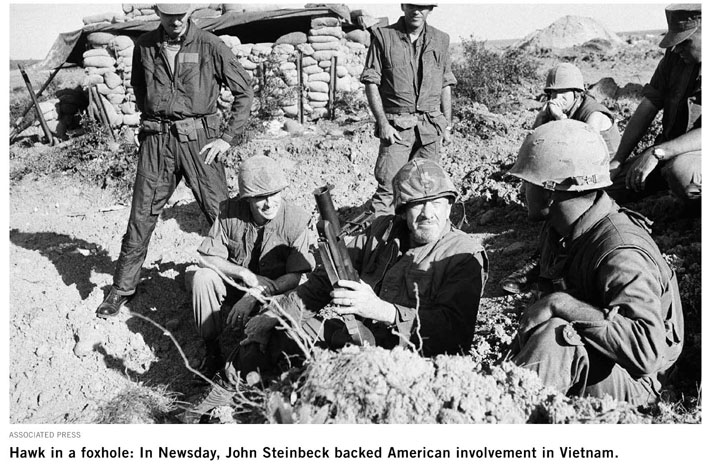

Steinbeck was looked upon as a “hawk” who openly supported the American involvement in the Vietnam War that he called a heroic venture. His warlike attitude appeared objectionable to the American public and also within his own family circle. In the U.S., Steinbeck was not only hated by the intellectuals of the right but some of the left had no hesitation to brand his stance as a “betrayal”. [2]

Picture 4: left, “Steinbeck the hawk” with rifle, helmet, flak jacket in a foxhole at a battlefield in South Vietnam. In his letters written from the frontline and sent to the paper Newsday, Steinbeck unequivocally expressed his support for the participation of the American Armed Forces in the Vietnam War. [source: Associated Press ]; right, Steinbeck’s son John IV (at the bottom of the picture), in contradiction to his father, was a fervent anti-war advocate. John IV later became a disciple of the Coconut Monk on the Phoenix Island on the Mekong River, Mekong Delta. [ source: Gale Literature Resource Center ]

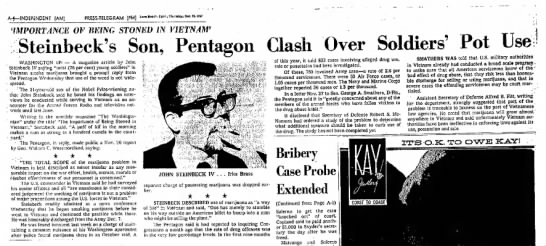

John Ernst Steinbeck IV [06/ 12/ 1046 – 02/ 07/ 1991], at the end of his draft he was discharged on 07/12/1967. Following a brief stay in the U.S., John IV returned to Vietnam in 1968 as an anti-war reporter – totally at odds with his father. John IV collaborated with Sean Flynn [actor Errol Flynn’s son] to set up the Dispatch News Service disclosing extremely detrimental news to Washington like the My Lai massacre, the Tiger cages on Con Son island…

While his father was still living, on March 05, 1968, in the aftermath of the Tết offensive, John IV testified before a Senate subcommittee revealing things that no American officials wanted to hear such as: “about 60% of the American soldiers between the age of 19 to 27 smoked Marijuana, and MACV itself encouraged drug addiction among the troops by providing them with habit-forming drugs like Amphetamines also commonly known as pep pills to soldiers in combat”.

[Wikipedia John Steinbeck IV]. A big press scandal ensued leading to a clash between the Pentagon and John IV.

Picture 5: Steinbeck’s son who served in Vietnam differed with his father. Early in March 1968, John IV testified before a Senate sub-committee that the war was a mistake, GIs turned into addicts, reports of casualties falsified… It was a mess that needed to end. Importance of being Stoned in Vietnam, Steinbeck’s Son, Pentagon Clash Over Soldiers’ Pot Use. Page A4 of the Independent AM Press-Telegram PM [Long Beach, California Thursday 28.12.1967]. [2]

The “Father and Son” schism in the Steinbeck family reflects faithfully that of the country throughout the Vietnam War.

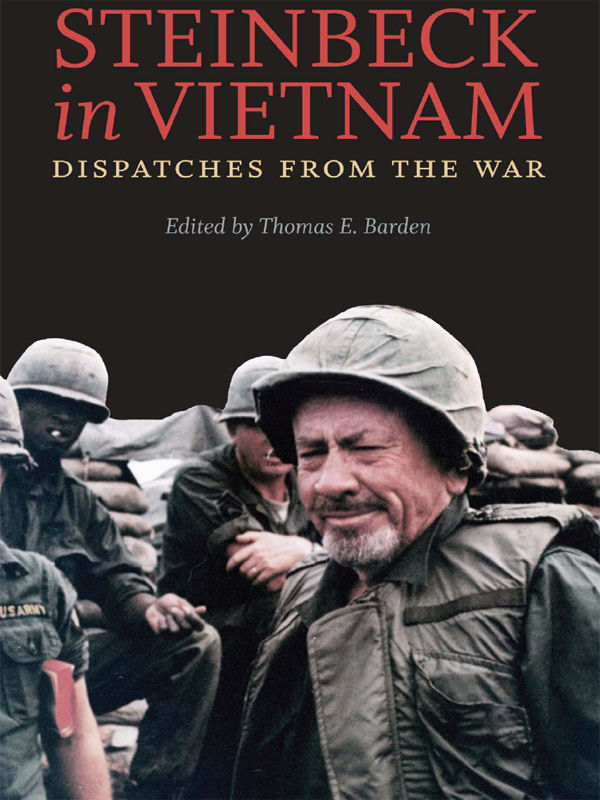

“Steinbeck in Vietnam: Dispatches from the War” [1] (University of Virginia Press, 2012), could be considered as the last contentious work penned by Steinbeck as he neared the end of his life at the age of 64.

John Steinbeck was diagnosed with cardiovascular disease but declined undergoing a heart bypass surgery. He passed away of heart failure in New York on 12/20/1968, in the midst of the1968 flu pandemic. He was a heavy smoker for many years in his lifetime.

STEINBECK AND A GLIMPSE OF VIETNAM

An Khê, Vietnam 12/22/1966

An Khê is a town in Gia Lai province in the Central Highlands located near National Route 19 between Pleiku and Qui Nhơn. It held an important strategic value during the Vietnam Conflict. Since August 8, 1965, the Americans built Radcliff to serve as the main base of the US 1st Cavalry Division. Radcliff was handed over to Vietnam at the close of 1970 as part of the Vietnamization of the war in preparation for the American withdrawal.

Three days prior to Christmas [22/12/1966], Steinbeck visited the An Khê base. With the aura of a Nobel Prize in Literature laureate, Steinbeck, at 64, looked seasoned in his GI uniform. During the night, he sat on a wooden box, surrounded by a group of young enlisted men, about his son’s age, who gathered to hear him speak. In a frank speech, Steinbeck confided: “Six months ago I was sorry that my sons had to go into the Army. But then, by God! Six months later I am proud of them because they are men, Men are really valuable things today.” [3] At the time, one of his sons was stationed in Pleiku; the other at Fort Ord, Monterey California.

On one occasion, a reporter asked: Is America locked in a hopeless war? Steinbeck replied: “That’s a most laughable question,” he added: “All wars are hopeless but necessary, and this war is also necessary.”

In the exchange, John Steinbeck answered all the questions coming from the GIs about his past except the too personal ones. He revealed he used to work as a longshoreman, lived with the paisanos, picked cotton, also the interesting detail that he did not use a typewriter to write. All his works were done in longhand.

Picture 6: John Steinbeck looking old and tired at Radcliff base, An Khê talking with a group of conscripts about his sons’ age three days before Christmas on 12/22/1966. [source: Ray Belford / Stars and Stripes]

"Some of the questions that you asked I wouldn't have answered most people, but I admire what you kids are doing here and I think that I owe you that respect," he said.

After two hours and two cups of coffee, Steinbeck was completely exhausted. He was compelled to excuse himself with the riveted young audience in order to take some sleep. A young conscript who attended the entire session, summarized his feeling this way: “He just seems to radiate greatness.” [3]

Pleiku, Việt Nam 01/07/1967

On January 7, 1967, during a visit to Pleiku, John Steinbeck observed the war actions from a UH-1B Huey helicopter and did not mince his words in effusive praise of the helicopter crew:

“I wish I could tell you about these pilots. They make me sick with envy. They ride their vehicles the way a man controls a fine, well-trained quarter horse. They weave along stream beds, rise like swallows to clear trees, they turn and twist and dip like swifts in the evening. I watch their hands and feet on the controls, the delicacy of the coordination reminds me of the sure and seeming slow hands of (Pablo) Casals on the cello. They are truly musicians’ hands and they play their controls like music and they dance them like ballerinas and they make me jealous because I want so much to do it. Remember your childhood’s night dream of perfect flight, free and wonderful? It’s like that, and sadly I know I never can. My hands are too old and forgetful to take orders from the command center, which speaks of updrafts and side winds, of drift and shift, or ground fire indicated by a tiny puff or flash, or a hit and all these commands must be obeyed by the musicians’ hands instantly and automatically. I must take my longing out in admiration and the joy of seeing it”. [1]

Picture 7: On January 7, 1967, John Steinbeck on an observation flight of the Vietnam War aboard a UH-1B “Huey” helicopter, of the 10 Air Cavalry Regiment based in Pleiku. Next to him was the gunner of a M60 7.62 mm machine gun. Several days after the Tết Offensive, Thomas Myles Steinbeck, Steinbeck’s eldest son, also a helicopter door gunner was sent to Vietnam [source: Associated Press]

STEINBECK AND TWO UNDOCUMENTED ENCOUNTERS

Cần Thơ, Vietnam, December, 1966

Hoàng Ngọc Khôi MD, (Saigon Medical School - class of 1960):

“When John Steinbeck was awarded the1962 Nobel Prize in Literature, I – Hoàng Ngọc Khôi and my friend pharmacist Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Tập, we were working at the Military Medical School and also in charge of the Military Medical Journal/ Tập San Quân Y (TSQY). Bửu Tập got hold of a copy of Of Mice and Men (OMAM), and handed it to me after he finished reading it. When I returned it to him, Bửu Tập ventured: Why don’t we translate it then serialize it in the Journal. We went to work and started publishing it in the TSQY about mid 1963 using the English text of OMAM and the French text Des souris et des hommes for reference. Author Trần Phong Giao, the then secretary of Văn Magazine, somehow read it and hurriedly went to talk with both of us. He gave us a down payment with the understanding that when the book was completely translated Văn Magazine would have the sole right to publish it. I did not know if Văn Publishing House had contacted John Steinbeck or not, but from what I knew there was no copyright agreement at that time between the two countries.

When Steinbeck arrived in Vietnam, I was the Head of the Military Hospital Trương Bá Hân in Sóc Trăng. At that time, there was an American captain who acted as advisor to the IV Division’s Department of Logistic/ Cục IV Tiếp Vận responsible for supply needs of the Military Hospital TBH. About every two months or so he would come to check if we were short of anything at the Hospital. For some unknown reason to me, he was aware I translated OMAM.

Suddenly one day, either at the end of 1966 or start of 1967, that captain (I no longer remember his name) came to the Hospital by helicopter and advised me that John Steinbeck was in Cần Thơ. He said he had an appointment for coffee the following day with Steinbeck from 2 to 3 in the afternoon and asked if I wanted to join them. He added I could go with him on the helicopter if I wished but would be on my own for the return trip. I was extremely excited and told him since it only took about more than one hour by car between Sóc Trăng and Cần Thơ I would drive my Jeep and see him the next day.

The following day, at the appointed time, the American captain was at the Military Hospital Phan Thanh Giản in Cần Thơ and drove me to an American Officer Club. We arrived at the same time as Steinbeck who was dressed in a combat fatigue and flak jacket. His beard and moustache were well trimmed. At the time we met, I was a Medical Captain, he called me Doctor and inquired if I had ever been to the U.S. and why did I choose to translate his book OMAM? I replied I visited his country twice and each time was very anxious to return to Vietnam because I missed my country and friends. He smiled and explained that was exactly what he intended to convey in the book. It’s about the desire to have a piece of land, a garden and having friends to talk to everyday. I brought with me two copies of the Vietnamese text, an English text of OMAM and a French text Des souris et des hommes and asked for his autograph for me and Bửu Tập. I also presented him with a copy of Of Mice and Men translated into Vietnamese. The captain only gave me half an hour with Steinbeck so I only asked him if he planned to meet with a Vietnamese author on his trip? He answered that his visit this time did not have anything to do with literature. He was mostly interested to carry out a field trip to learn about the situation in the South and find out if this war is winnable. On that day, the captain took a polaroid photo of me and Steinbeck. Half an hour went by very fast and Steinbeck only stayed six weeks in Vietnam. In such a short time he had to go to four military corps and write daily reports to the newspaper Newsday he worked with as a special reporter. Steinbeck supported the U.S. sending the troops to stop communist expansion and hated the anti-war protestors. On the other hand, his son who was serving in Vietnam with the U.S. Army News Corps very much opposed the war. The reports he wrote from Vietnam were later compiled into a book titled: John Steinbeck in Vietnam: Dispatches from the war. And you [the author] already know that.

Picture 8: left, the English text of Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck; center: the

French text Des souris et des hommes of the same work; right: the Vietnamese text of Of Mice and Men translated by Hoàng Ngọc Khôi and Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Tập, Văn Publisher Sài Gòn 1967. After 1975, this Vietnamese translation saw several reprints in Vietnam.

On the night of April 29, 1975, I unexpectedly left Vietnam on a Navy ship unable to bring anything with me. After 1975, a relative in Vietnam sent me a Vietnamese copy of Of Mice and Men by the Hội Nhà Văn Publishing House. It was the second edition with the date 1997. The last page in the book stated: “We have tried several times to contact the Messrs. Hoàng Ngọc Khôi and Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Tập. Regrettably, to this date, we have not heard from the two translators”. Afterwards, I received a later edition of Of Mice and Men from home. This time the publisher was Văn Học and the year 2001. I later heard that the book has gone through several reprints because it was used as reference materials in the English departments of the universities in Vietnam. Sadly, my friend who co-translated OMAM with me, pharmacist Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Tập, is no longer with us [1930-2020]. Hoàng Ngọc Khôi MD, Toronto, Email dated 03.21.2021

Tây Ninh, Vietnam, January, 1967

Trần Văn Khánh MD, (Saigon Medical School – Class of 1965)

Doctor Khánh, former intern at various hospitals, was a classmate (1965) and dear friend of Nghiêm Sỹ Tuấn. Tuấn worked closely in the Ban Quan Điểm/ Editorial group of the Tình Thương Journal of the Medical School. Upon graduation, they were drafted into the military with the rank of medical first lieutenant. One of the rare neurosurgeons at the time, he was assigned as chief surgeon of the Military Hospital at Tây Ninh. He recalled: During those days, considering the high frequency of the engagements, casualties on both sides shot way up. I worked day and night at the Military Hospital as well as the civilian one! I performed all kinds of operations including stellectomy using field instruments at that!”

“I had the pleasure meeting author John Steinbeck in Tây Ninh in 1967 under extraordinary circumstances! I do not remember the exact date of that providential event. During my morning rounds seeing the post-op patients, by total coincidence, I saw a Jeep with three Americans on it driving into the Military Hospital. Two men and a woman. They needed to wash their hands and use the toilet. I immediately recognized author Steinbeck thanks to his beard, moustache and his farmer’s face. He looked weathered in a GI’s uniform complete with bullet proof vest and helmet.

After a few exchanges, Steinbeck was quite surprised meeting a native who could speak fluent English and recognize him. On top of that, one of his faithful readers over the years. Khánh mentioned the book The Grapes of Wrath, referring to the passage of a mother who just had a miscarriage but bravely tried to save the life of a starving man by letting him suck milk from her breast. Khánh told Steinbeck that the last page was not only powerful, tender and extremely beautiful as well. Once read it could not be forgotten”.

That’s enough for Steinbeck to be smitten. He cordially invited Khánh – whom he called “young man” - to get on the Jeep and go visit a Special Force camp not far from the foot of the Bà Đen Mountain the American soldiers named the Black Virgin Mountain. It is also the place Steinbeck believed to be the end point of the Hồ Chí Minh Trail.

The deepest impression this experience left in Khánh: Steinbeck showed he was an ardent war advocate, convinced that with their modern, state of the art weapons the Americans will defeat that backward, rag tag group of Vietcong. Meanwhile, the silver hair American lady – Khánh did not know whether she was his newly wed wife or not – who sat in the back was furiously recording each and every of his words.

It is not that his memory failed him but Khánh is unwilling to speak much about that field trip with Steinbeck. Khánh felt it was a personal experience and wished to keep it that way. He wrote: “I wish to decline to bear witness to an internecine war and historical time that saw the North conquer the South”. After he moved to the U.S., Khánh had the opportunity to visit The National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, the city of Carmen, and the chance to embrace the bust of Steinbeck.

A BOOK THAT BEGETS CONTROVERSY

The “Letters to Alicia” that appeared on the paper Newsday were later compiled into a book entitled Steinbeck in Vietnam: Dispatches from the War. It was not published in the 1960s, for fear it would damage Steinbeck’s reputation. Only 44 years after his death (1968), that the University of Virginia Press decided to publish it (2012). The preface and epilogue of Steinbeck’s last book was written by Thomas Barden, a professor at the University of Toledo, Ohio who was a Vietnam veteran and a scholar on Steinbeck’s works.

According to Barden, President Johnson himself wanted Steinbeck to go to Vietnam and report the events from the field. Steinbeck intended to do it as an independent observer but the content of his letters clearly demonstrated his support of the war reflecting President Johnson’s policy at the time and his Domino theory as well as the winnability of the conflict. John IV testified before a Senate sub-committee that the war was a mistake, GIs turned into addicts, reports of casualties falsified…It was a mess that needed to end.

At the end of his stay in Vietnam, Steinbeck returned to the U.S.. In his personal contacts, he vented his displeasure that the American public was fed daily inaccurate news about the war. His wife Elaine also advised him he needed to change his view about the Vietnam War but he did not have much time left to write about it.

Whether one agrees with John Steinbeck or not, he has completed his mission in life. His entire works can be found on the shelves of libraries or schools. They represent a lesson he offers to future generations.

Picture 9: The book cover of “Steinbeck in Vietnam: Dispatches from the War” was not published in the 1960s, but only 44 years after his death. University of Virginia Press (2012).

IN RETROSPECT

In 1972, I was participating in a training program in San Francisco for the specialty of rehabilitation medicine. John Steinbeck died four years before in 1968. President Lyndon B. Johnson was succeeded by Richard Nixon who was implementing his program of Vietnamization of the war – the American news media called the plan an attempt to “change the skin color of the corpses” in preparation for a complete American withdrawal from South Vietnam.

The anti-war movement with its teach-ins, sit-ins reached its peak and made its presence felt at all the U.S. campuses. At the University of Berkeley, the South Vietnamese students who were sent by their powerful and wealthy parents to study at the school joined their American classmates to protest against the war. Wearing black pajamas, they organized sit-ins, sang the song “Quảng Bình Quê Ta ơi,” organized fund drives to support Hanoi and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. And somewhere in America, Steinbeck’s two sons were undoubtedly marching along.

In 1972 and subsequent years, I visited Monterey and Salinas, Steinbeck’s hometown. He passed away in New York. Subsequently, his bones were brought to California and quietly buried in the family cemetery. Thirty years later, the National Steinbeck Center was inaugurated (June 27, 1998) in Salinas, his hometown.

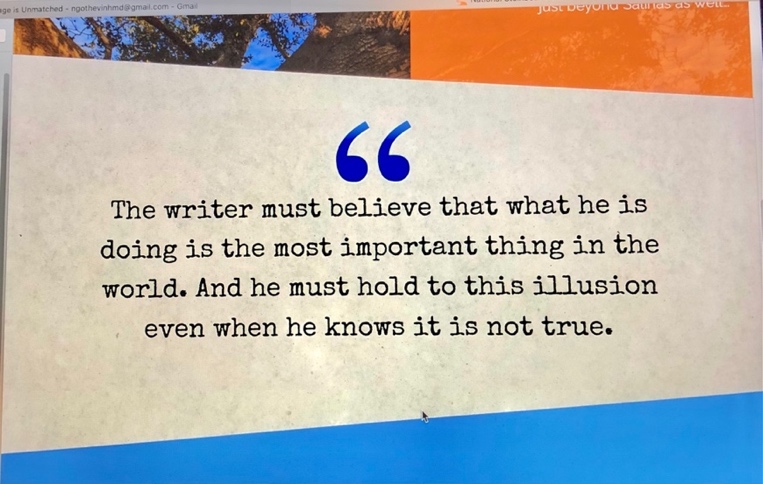

Picture 10: upper, the National Steinbeck Center, [address: 1 Main Street, Salinas, CA 93901] in Salinas his hometown. The Center was built and inaugurated (1998) 30 years after his death (1968); lower, a quote from John Steinbeck was enlarged and displayed at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California.

On one of the visits, the thing that remains engraved in my memory is the blow up of a quote from John Steinbeck that was displayed in the lobby of the National Steinbeck Center Salinas, California.

“The writer must believe that what he is doing is the most important thing in the world. And he must hold to this illusion even when he knows it is not true.”

Naturally, this is not Steinbeck’s best quote but probably it reflects the most his journey of 66 years on earth. A life full of vicissitudes and contradictions that he stubbornly chose to propel him to the apogee of success and at times against his own self.

Picture 11: The bronze bust of John Steinbeck in Monterey California, his hometown.

NGÔ THẾ VINH

Monterey, California 04/01/2021

REFERENCE:

1/ Steinbeck in Vietnam: Dispatches from the War, March 29, 2012 by John Steinbeck (Author), Thomas E. Barden (Editor)

2/ Steinbeck In Vietnam: A Great Writer's Last Reports, April 21, 20126:25 https://www.npr.org/2012/04/21/150012711/steinbeck-in-vietnam-a-great-writers-last-reports

3/ War hopeless but necessary, Steinbeck says. Ray Belford, The Stars and Stripes Archives, December 22, 1966

https://www.stripes.com/news/war-hopeless-but-necessary-steinbeck-says-1.84079

4/ John Steinbeck, despised and dismissed by the right and the left, was a real American radical. America’s Best Hated Author by Eric Johnson. Aug 5, 2004

https://www.montereycountyweekly.com/news/local_news/john-steinbeck-despised-and-dismissed-by-the-right-and-the-left-was-a-real-american/article_4bd65e88-6803-59da-9ec2-0a62c5c8adbb.html

5/ John Steinbeck IV and the Coconut Monk. Alison Teal, Contributor 04/09/2014, HuffPost

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/john-steinbeck-and-the-co_b_5089375

6/ (A) The Dragon in the Jungle: The Chinese Army in the Vietnam War. Xiaobing Li. Oxford University Press, Jan 30, 2020. (B) A History of the Modern Chinese Army. Xiaobing Li. The University Press of Kentucky, 2007

7/ Of Mice and Men. John Steinbeck. Translation by Hoàng Ngọc Khôi và Nguyễn Phúc Bửu Tập. Nxb Văn, Sài Gòn, 1967

8/ Explore Vietnam

Underground secret tunnel at Lạng Sơn has many notes in Chinese characters and https://youtu.be/mpuudi8AMIU

9/ Great Writers of the West: Steinbeck and the Environment. The Bill Lane Center for the American West. Stanford University Wednesday , May 10, 2017 https://west.stanford.edu/events/great-writers-west-steinbeck-and-environment