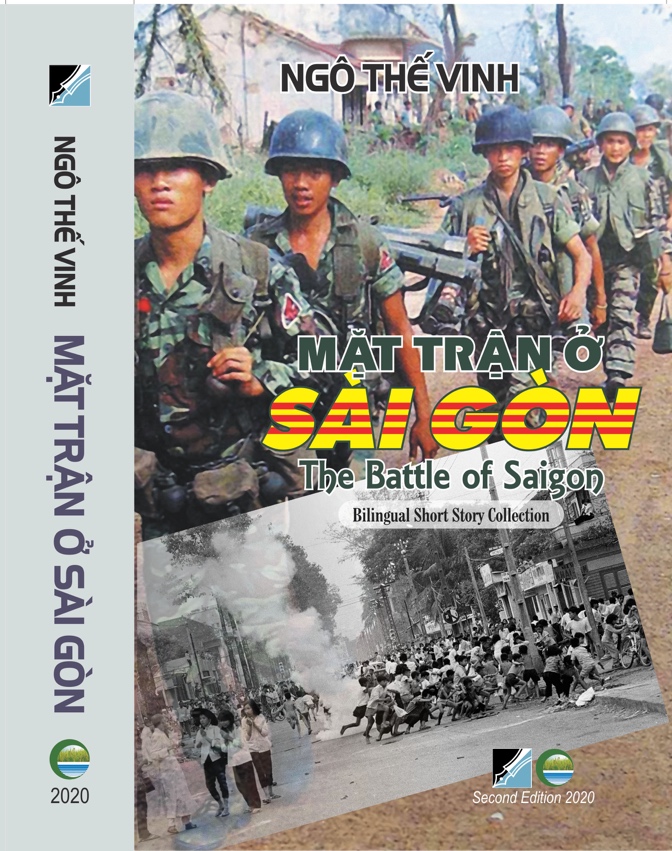

of the bilingual collection of short stories “The Battle of Saigon”

Nguyen Thi Khanh Minh

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NGO THE VINH,The Wounds That Had Not Really Healed *

After reading the first story “The Battle of Saigon” which is also used for the title of the book by Ngo The Vinh, my immediate desire is to learn more about the heroes whom he mentioned in the story: like what happened to them, where are they now. I really wish to convey to them, though quite late, my admiration, gratitude and sadness as well. And right away, I also would like to let the author know I fully share the thoughts of the antagonists in the story:

… “Hawk” is the nickname the chief surgeon conferred upon me for my warlike tendency. It appears to me that everyone present is irritated with news of trouble in Saigon... He continued:

“When you are back there, Hawk, if you meet any discontented students, just pick them up and deliver them to me at Fire Base 7.

Holding his wine glass as though he wants to break it in his hand, Major Binh, the pilot, says in a sharp tone of voice, “Left it to me, you won’t need waste any tear gas grenades and rockets. I’ll need only have a few heavy machine guns set at street corners to await them.

It seems that politics divides us in some fashion.

The major turns to the doctor: “Well, how about you, Dr. Zhivago? What do you think about those students who do nothing other than engage in disturbing demonstrations?” (The Battle of Saigon pp 270-271)

Back then, in the years 1971-1972, the above paragraph would make me very dismayed with the attitude of those soldiers. I was then a second-year student at the Law School and a sympathizer of the students’ anti-war movement. We truly resent the soldiers and disparaged them as a bunch of soldiers, policemen, bullies of the demonstrators. In those days, in our eyes, the idealistic way of life was to be against the war, boycott classes, take over the streets, oppose the government, and… listen to anti-war music.

Who set the whole thing up and managed to influence the mind of our youth at that time? The way it was set: all we knew was to oppose or condemn the war while turning a blind eye to the suffering, tragic lot of the soldiers who were making the ultimate sacrifice in a struggle being opposed everywhere! It is a pity I did not have the chance to read this work then. Come to think of it, it was the fault of the information, civic proselytizing service of the Republic of Vietnam that has misjudged the true significance of the book leading to its ban and the prosecution of its author. In fact, if more people were able to read it, right from the start, the schism between the military and people could have been averted. Instead, it could very well serve as a bridge effectively connecting the frontline to the rear and building a powerful solidarity. How unfortunate it was!

If, at that time, the South could see things like Phuc:

“… Being an anti-war person, Hoang had the tendency to condemn only one side in the war. Unable to hold back his irritation, Phuc retorted, “What good is it to condemn only one side concerning an act of war, other than discourage those who are fighting for a good cause?” (Quiescence on the Battlefront p. 332)

They did not properly perceive to both oppose the brutal inhuman side of the war, and at the same time, take a clear stance that it was the war to protect the survival of South Vietnam. On the other hand, in the North, they established a firm solidarity between the soldiers and people. The result… the fall of the South, the disbandment of its armed forces. Were they not for authors like Phan Nhat Nam, Cao Xuan Huy, and in this case, Ngo The Vinh with his The Battle of Saigon, the epic, heroic sacrifice of these warriors will never see the light of day and touch the heart of us all? Absent a proper recognition of a true measure of their sacrifice, we would still owe them a true and just reassessment, we would still owe them an appreciation, a tearful show of respect. Theirs is not a nameless army that can be allowed to fade into oblivion like that. They are true heroes. They have died for the country and their souls are hallowed. It may be already late in coming, but their story must not remain untold. Certainly, when writing those stories, Ngo The Vinh must be peeling, with great pain, one scab at a time on the wounds still bleeding in his consciousness.

Like a smouldering suture

It sticks to his chest

Gently he peels off the scabs

Turning stitches into loose leaves …

(Trần Mộng Tú – His Non-Bleeding Wound, p. 255)

Pick up that book, turn it page by page, gently as if undressing a wound …

Looking at the youthful faces of those soldiers on the front book cover with the caption “To all those who never made it back.” I could barely hold my tears… I took a brief breath realizing full well I need to pluck up my courage to enter the world of Ngo The Vinh, an author about whom Hoang Ngoc Nguyen wrote:

“To an author like Ngo The Vinh, who since childhood could already learn the early lessons of freedom-seeking migration from the north to the center and finally the south of the country; who was schooled from the well-famed Khải Định (named after a king), Huế, to no-less-prominent Chu Văn An Highschool (Saigon) and the Medical School; and who spent years serving as a medical physician in the front line of the remotest and bloodiest battlefields in the Trio-Border of Vietnam-Kampuchea-Laos until the fall of the nation... his life alone is abundant enough without the loan of any imagination.

Narrative reports are probably the most suitable style for Ngo The Vinh. He had enough pride and confidence in himself to speak up and find ways to express what he had witnessed and share his judgments and remarks that listeners and readers could accept. On the other hand, he also had the necessary humility of a person who understood the human helplessness in confronting "immense sufferings" in life that "Buddha’s Tears" only turned helpless the pitiful and grievous human "karma". (Hoang Ngoc Nguyen – In Search of peace with “The Battle of Saigon”, p. 509)

Truly, his writing came directly from his life experience. Consequently, his thoughts, feelings permeated his writing style and his words animated the readers’minds and hearts to immerse them in the joy, sadness, pain, anger he felt. The words that Ngo The Vinh uses spring out of real life. The style that Ngo The Vinh writes reveals a tragic if not outright plaintive beauty. A beauty that emanates from his sincerity of heart; humanist feelings; compassionate nature; wise, deep and placid understanding. All these attributes contribute to a compelling, realistic, persuasive penmanship in the person of Ngo The Vinh. Moreover, that penmanship does not lack a poetic touch that allows the readers some room to breathe, a moment of respite even while reading the direst circumstances of the stories.

In the first story, The Battle of Saigon, the past reemerges for the readers to take a new look at everything. To reimagine the person, one was in one’s twenties, the most beautiful years of one’s life. Regrettably, that time Hoang Ngoc Nguyen called “we have only one time to live” had gone by leaving behind so many painful scars. Oh, my friends in my twenties, where are you now, have you read The Battle of Saigon, so that like me, we can face the past and find some closure for ourselves…

In my story Lần Theo Mộng Ảo Mà Về, in 2013, I wrote:

“… in our college years, with books as sole companions, one day, to our astonishment, we, coeds, set foot on the campus and wondered: “Why are the classrooms so empty?” “Where are all the boys?” If my memory serves me right, it was in 1972. The mobilization to fill the ranks swung into action full force. I finally hit an immovable wall that brought me face to face with reality. For how long have students in Saigon like me lived on the sideline? For how long? For a long time, the inhabitants of Saigon were convinced that the city is an isolated island that the tentacles of war could never touch. How many were those who believed that the march of bullets, ideologies will stop at their city limits? I felt ashamed and guilty... I felt like an unwitting spectator who knew nothing more than pronouncing meaningless slogans when the blood of our people on both sides of the conflict have been spilled and young men sacrificed at the frontline.”

That’s the way it was. I grew up during wartime, and after the “upheaval of 1975” that transformed the country ran its course, I finally opened my eye to many things… Back then, when the towns and Saigon, capital city, were still untouched by hostilities, quite a few residents behaved as if their cities and the battlefields were two separate entities. The soldiers were well justified when they entertained these thoughts:

… What is more, in this motherland, …there is a separate society above and beyond them, magnificent and gloriously bright, and immersing itself in its detached happiness. This separate society is a world that alienates itself from the soldiers, soaks itself in pervasive fragrance and excessive consumption. Here we have the world of a group of people clamoring for war while managing to stay above the fighting or remaining outside of it.

Eventually, these bewildered soldiers ask themselves ‘what’ they are protecting… They cannot imagine protecting a luxurious pleasure boat traveling down a narrow river stained with blood and dotted with the floating corpses of their fellow countrymen. Neither can they find any acceptable reason to protect the leisurely life of a small fragment of high society, to secure the environment of care these privileged people lavish on their favorite dogs, on their stud horses… care which surpasses anything the wretched mass of humanity has ever dreamt of. These young soldiers who are ready, always ready, to sacrifice their lives fighting the enemy in the battlefield, cannot stop wondering why they are pulled back to the capital. How can the dreams and aspirations which we hold for a military career manifest themselves only through turning us into security guards for the rich, into a type of highway police directing traffic on the flow of history?” (The Battle of Saigon, pp. 273-274)

So that we can empathize with the soldiers guarding the capital: … that our prospective battlefield will not be the mountains and forests of the Central Highlands, instead, what we are actually to encounter is a battle in the capital city… It may appear to the soldiers that the right battlefield is not the one far away in the border areas of the highlands, but the truly challenging battleground found in Saigon. (The Battle of Saigon, p. 275)

But ironically, they felt like a herd of lost wild animals roaming the city’s streets: … “without confessing it, every one of us feel weary even before actually placing ourselves in that dull battlefield, Saigon. Thoroughly familiar only with mountains and forests, the soldiers under my command will be no different from wild animals in the city, bewildered and lost.” (The Battle of Saigon, pp. 272-273)

How much strength did they consume when they were alone in the rear? They should normally be reenergized while staying in the city instead! And not many participants in those demonstrations could sympathize with the conflict raging within the minds of those soldiers assigned to keep order in the capital city.

“… If it clearly turns out that my assigned duty involves a long-term stay in Saigon, I will ask permission to be released from our unit and transferred to a certain hospital in the highlands. This is in spite of the fact that I have constantly thought of our combat unit as the one and only place I would choose to spend the entire period of my military service… On the one hand are the soldiers he cares for as required by his duty; on the other hand are the youths and students who participate in anti-government demonstrations colored with a touch of anti-American sentiment, and whose viewpoint he accepts and shares to a certain degree. Clearly, we all are but small cogs in a large machine.” (The Battle of Saigon, pp. 271, 272)

The “We” used by the protagonist the doctor encompassed not only you, the soldiers, but also us, the entire people of Vietnam living under a system that endlessly drafted and fed its youth to the war machine… so that we were only capable of passive acceptance as one would nominally embrace fate, going straight into mindless killing… (Buddha’s Tears, p. 287)

In the context of the “Vietnamization of the war”, the U.S. decided to abandon its ally. How bitter and infuriating it is to watch the soldiers of the Republic of Vietnam having to fight in such circumstance as remarked by Tim Page: “… though there have been few that have told it from the South Vietnam point of view, from the aspect of the true losers, those who fought for and believed in the nascent Southern Republic. Ngo The Vinh brings us essays illuminating his experience as doctor with the crack rangers, here in dealing with the dichotomies of combat...” (TIM PAGE, Life – Time, UPI Freelance Reporter, p. 522)

… I was clearly aware that in a short moment, we would jump from our helicopter onto Cambodian land while the news was still fresh that President Nixon was about to go to Peking, that Moscow was preparing for détente with the U.S… In the end, what we would face was shameless opposition and animosity between two Vietnamese sides – another instance in the history of division, an inevitable tragedy… an arena wherein Vietnamese were brutal gladiators armed with ideological contradictions and ignorance… Not only because of the deadly effects of bullets and guns, but this was precisely a mental impasse which had made us incapable of thinking and reasoning on any issue. Our brains had been reduced to broken masses of grey matter, so that we were only capable of passive acceptance as one would nominally embrace fate, going straight into mindless killing. Perhaps the only thing left to us was the pulsation of the Vietnamese heart, a heart that had not changed, a heart that knew no joy and shared in a collective hatred… (Buddha’s Tears, pp. 286, 287)

… Vietnamese soldiers carrying rifles were conscious of having, with humiliation and complete loss of faith, to fight alongside an allied force which placed its own interests above the highest goals for struggle by the Vietnamese people. As for the North Vietnamese side, to sacrifice tens of thousands of troops to reach a goal of strategic value was something all too easy for them to do. Those were the reasons which urged us, while having to wield our firearms, to estimate for ourselves through a smokescreen the true measure of this war, in order that we would not transform ourselves in the last hours of the conflict into heaps of ashes. (A Turning Point in History, p. 297)

… Starting from a very simplistic naïve notion of serving the fatherland to the bitter end, by confronting and overcoming whatever obstacles and difficulties that might arise, I had not entertained the thought of dealing with politicking amidst the military collective, and had resolutely refused to have anything to do with it. But gradually, through repeated experience of rubbing shoulders with others, I had become deeply aware that wielding weapons was not the end of our line of duty; rather we were being forced into complicated circumstances of political entrapment. The time had come for a soldier to clearly define his position and ask himself for what legitimate reason he was sacrificing so much of himself in continuing to participate in armed conflict. (Peace Will Come No Sooner, p. 309)

COMPASSION, LOVE OF OTHERS IN THE BATTLE OF SAIGON

Coexisting intimately with the atrocities of the battlefields, witnessing the agonizing death of fellow comrades in arms, but still keeping calm when talking about the other side without any rancor, only factual description of the events, with an attitude of placid acceptance coming from a deep understanding of the fate of a cog in a machine that could be visited by death at any minute… I much admire in him the spirit of the “follower of the way,” of the “great man” that has its root in his compassionate heart. I quote:

… All our senses became alert again, disposed to action. We were poised on a hair-trigger, tense with the demeanor of those set for offense. There would be precious little discrimination on the battlefield... Guns and bullets would engage in no dialogue. There would only be Vietnamese of fortitude – from both sides – who volunteered to offer their bodies as torches to heat up the Indochina war (Buddha’s Tears, p. 287). I want to highlight the phrase There would only be Vietnamese of fortitude – from both sides … How many of those who wrote about war could show such fairness to the enemy?

… And this year, according to the government’s spokesman, the Đông Xuân or Winter-Spring campaign alone, at its peak during the rainy season, dealt a devastating blow to the communist fighters... (The Battle of Saigon, p. 264)

The terms he used to write about the opposite side denote a dignified demeanor, you and me, sharing the same fate, in a confrontation he viewed with some bitterness: - In the end, what we would face was shameless opposition and animosity between two Vietnamese sides. (Buddha’s Tears – p. 287)

His compassion shines out the best in the short story Peace Will Come No Sooner: coming back from a life and death ordeal in the old jungles in the Highlands in 1971, the antagonist Grey Tiger could still find in his heart the ability to deal with the prisoner in a very peace-like, humane way.

… The man was very young, his skinny, pale body quite in contrast with the alert facial expression and the deep passion in his eyes. He evoked the image of my younger brother who had been killed in battle not long ago... There arose from the depths of my heart a sentiment very hard to describe, somewhat like a combination of anger and compassion. But then his childlike face immediately settled my feelings… This approach, in fact, was not merely because of the necessity to extract intelligence from him, but simply because I felt I had the duty to save his life. The look in his eyes betrayed his trust in me… As for myself, I still honestly believed that he would be all right until the time he would accompany the company to the base. Moreover, in my heart I had the wish to be present, to have a role to play in the handling of this particular young man, which I thought would be rather different than usual. (Peace Will Come No Sooner, pp. 311, 312)

… when from afar the sound of the approaching helicopter squadron was heard. Soon thereafter, for some unknown reason, suddenly the prisoner sat bolt upright and screamed in panic. As if he could not see, the man blindly extended his arms straight in front of him and got hold of me. Apparently in terror, he called out a single word: “Brother!” before he collapsed and died instantly... My hand reached out and pressed upon his eyes. The still warm eyelids closed without resistance... Go to your last sleep now, I said gently beneath my breath, even as I was aware that never before had I felt so intimate and familiar with death. (Peace Will Come No Sooner pp. 313, 314, 315)

In war, death can come in many unimaginable shapes and forms. Like the case of the mentioned prisoner who died just because of the sound of a landing aircraft or from a booby-trapped corpse or even the unjustified death of fellow comrades mistakenly killed by friendly fire with their faces disfigured by missiles.

Please read the following moving paragraph to ponder about the futility of Grey Tiger’s sentiment that nevertheless still gives us some hope in the existence of the humanist nature in man – My throat constricted painfully and my heart wearied, but I could not shed even the drop of tear. In the inmost recesses of my heart, I truly wanted to be able to cry. - (Peace Will Come No Sooner, pp. 315-316)

What could it be if not our love for our brethren? If not, then what would it be? And here is a very good paragraph that reminds me of the desolation of a battleground with “forlorn mounds, humming wind” (Chinh Phụ Ngâm) that helps me appreciate more fully the “numbness, emptiness” the protagonist felt looking at the lonely corpse of the prisoner on the ground below.

… As for myself, I felt it cruel to leave the dead body behind. When I as the last person had entered a helicopter, the aircraft hurriedly shot up into a gloomy sky where storm clouds were rolling in without pause. Viewed from this height, it looked as though the corpse was deep in a peaceful sleep, covered not with a flag but with a pale green hammock. I was resigned to leave him there alone, alone with the isolated mountain and the surrounding jungle, and carried with me an indescribably disquieting emotion. How I wished I had had enough time to dig a grave for him, even one just barely deep enough to enfold his body.

Sitting next to the door, I felt the strong prop blast forcefully splashing moisture from the clouds against my face, making it cold and sore. My skin and flesh numb, my heart numb too, numb almost to the point of insentience, I could neither think thoughts nor respond to anything... the sergeant, who was my close and reliable aide, raised his voice and reminded me. “I think you forgot something, Grey Tiger,” he said. “No, I did not forget about it this time around,” I assured him. He was referring to the practice of planting a grenade with the safety catch undone under the body of the dead prisoner left on the LZ. More than once the enemy had done that and caused us much damage. But this time, I thought that even if I had used his corpse as another trap and caused a few more deaths, that would not make Peace come any sooner. (Peace Will Come No Sooner, pp. 316, 317)

THE ROMANTIC PAUSES AMIDST THE HOSTILITIES

Next to the tragic, touching camaraderie, the tense suspense of the battlefield I referred to above, one can find passages full of charming melancholy giving the readers time to take a break. Under Ngo The Vinh’s uniform, lives a poet, an extremely sensitive and compassionate one. During his operations, that soldier poet recorded the thoughts, emotions he experienced before him with a perceptive pair of eyes and a style that liked a lamenting fiddle sings the harmony between the soul and its surrounding.

… every year at the beginning of the wet season, together with fellow ARVN units from the lowland, our unit converged on this mountainous area to encounter big enemy divisions with whom we competed for control of a few denuded hills, value running through an uninhabited area… (The Battle of Saigon, p. 264)

How do you react to the use of the word “encounter” to refer to an engagement, a firefight? Is it intentional that Ngo The Vinh the military tried to reduce the risk of the readers suffering a stroke when he was about to lead them into the horrors of combat? The allegories, the verbs selected by him are very descriptive, beautiful, uncommon but exquisitely precise. They bring tears to my eyes. It is the compassionate soul of the poet that gives him the ability to enter into communion with his surrounding even when caught in the jaws of death.

… Early in the morning of D-day, the day of the insertion operation, when the mountains and forests surrounding Hill 1003 were still wrapped in a thick fog, while the doctor’s comrades were holding their breath in great anxiety, from above the clouds a small OH-6A Cayuse light observation helicopter, like a gently falling leaf, landed on the base safely… (The Battle of Saigon, p. 268)

... a pilot’s corpse retrieved from the jungle by helicopter, drooping from the sling like dead game being pulled up. (The Battle of Saigon, p. 270)

… Detaching from the fleet and gradually decreasing in altitude, the helicopter which was tasked to insert the team wavered over treetops... (Buddha’s Tears – p. 287)

… The sky was the purest of blue, without a dark cloud to indicate imminent bad weather. Water of the rice fields shimmered highlights. We left behind us, in the distance, Black Lady Ba Den mountain – its existence no less than a mistake made by the Creator of the universe, a deformity embedded in the Delta’s otherwise unbroken topography – which protruded denuded from the green flat surface of the plain. The mountain embodied many mysteries and legends: a habitat of bloodsucking and venomous mosquitoes; a place of malignant malaria caused by plasmodium falciparum; a site of horrendous battles; a ground where were buried our fellow fighters during an operation four years ago. Engraved in my mind was the image of moonlit nights, nights when Ba Den’s lunar orb wore the pale face of one afflicted with malaria. (Buddha’s Tears, p. 282)

… Phuc recalled the day when he had first met Tom at one of those rice fields in Phan Rang which extended all the way to the rock-strewn foothills of the mountains, where herds of spotted goats ruminated. Standing high on top of a large rock, a male goat cut a sharp figure against the sky. Farther away, the deep blue ocean had been calm. Here and there slow-moving windmills were drawing seawater into fields of white crystalline salt… Gusts of hot wind swept over plots of land where the earth contracted by evaporation. Ironically, the rice fields after the flood were arid and shriveled up as though suffering from drought. (Quiescence on The Battlefront, pp. 326, 333)

… Down below among green fields curved roofs could be detected, a special architectural feature of Cambodian wats, their Buddhist temples. Cambodian villages did not look much different from Vietnamese villages, only more spacious. Many red-tile roofs stood close to one another, interspersed with dung-colored thatched roofs. Wispy columns of grey smoke rose gently from late afternoon cooking fires, children played, and buffaloes and cows returned to their padlocks. How much longer could that romantic scene last in an area of Asia still rather peaceful? Or had its better time already passed, after fifteen years of skillful swinging above a sea of fire by Prince Sihanouk? In the distance toward the south, the afternoon sun was scattering its golden rays over the Mekong river, so abundant with fish and silt. Rolling rubber tree forests blended into the wild jungle. Soon there appeared below us deserted villages marked with rows of craters left by B-52 bombers. In fact, no trace was detected of human or other living beings. Was I not seeing a repetition of Dakto, Khe Sanh, or Son My in Vietnam? I asked myself. To where had the armed struggle between Vietnamese opponents driven away the Khmer people born of those villages? Being carried forward by the intoxicating sweep of history, who would stop to consider the fact that war among the Vietnamese could widen its effects to diminish the glory of an ancient Angkor civilization? In the desolate quietness of an early evening, in one of those ruined villages, I imagined, there remained a certain unknown woman who resignedly sat holding and breast-feeding her baby. Was not that, after all, a most comfortingly beautiful and everlasting image which symbolized the significance of survival of the human species? (Buddha’s Tears, pp. 285-286)

What you just read is not the description of events and thoughts of a passenger on a tourist airplane but of a soldier about to be dropped into a firefight - so that we were only capable of passive acceptance as one would nominally embrace fate – the beauty here is dramatic, both tragic and noble – a reflection of Ngo The Vinh’s soul -just like the conclusion in Buddha’s Tears.

… Not very far from that same headquarters, in the northeast direction, after seven days lost in the jungle wilderness, two ghost-like figures made it with difficulty to a ruined village, the man slung over the shoulder of the other being near death. And throughout that night, in a deserted Cambodian wat, a Catholic ARVN soldier, exhausted and full of sorrow, knelt down by the corpse of his fallen companion. Directing his tear-filled eyes toward the serene face of the Buddha statue, he prayed with all his heart for the soul of his unfortunate comrade soon to be liberated. Outside, pounding rain raged relentlessly. Wind shook the long dark night enveloping the entirety of mainland Southeast Asia. (Buddha’s Tears – p. 290)

THE WOUND UNHEALED

Talking about pain, affliction in this book, we can read:

… It had been six years since the traumatic event of April 1975, but the skin-peeling pain of the experience was still as fresh as if it had been inflicted yesterday. (The Kim Dong Dream, p. 323) … could not discount the “bloodless wounds” pertaining to PTSD – post traumatic stress disorder - which Gumber had suffered in the years immediately following his return to the U.S. (In Retrospect, p. 370)

… the wounds that had not really healed (In Retrospect, p. 376) with the survivors.

… Phan wondered when he himself would really be liberated from the war that had belonged to the past for seventeen years. (Another Wall, p. 368)

… the news was still fresh that President Nixon was about to go to Peking, that Moscow was preparing for détente with the U.S. In the end, what we would face was shameless opposition and animosity between two Vietnamese sides – another instance in the history of division, an inevitable tragedy… (Buddha’s Tears – p.287)

A tragedy like a small scar that perpetually protrudes in your consciousness, each time you scratch it, it hurts. Besides the Vietnamese, more than 50,000 American soldiers lost their lives in the battlefields of Vietnam. Those who survived the long dark night (NTV) when they went home took with them many wounds both physical and mental. The legacy of war that prevented them from reintegrating with society in their own homeland.

… in his private world he [Jim] often had nightmares and re-experienced painful events of the war. Fury tore at his heart against the indifference, the lack of respect, which society showed him and other Vietnam veterans. “We should have been treated as heroes upon our return,” he exploded. (Another Wall, p. 365)

… There had been no shortage of parades swarming with the Stars-and-Stripes and splendid yellow ribbons to welcome home as heroes those soldiers coming back from the lightning Operation Desert Storm in the Persian Gulf, which lasted but a few weeks – as well as from some other wars. But the likes of such treatment had never been accorded to veterans returning from Vietnam after years of hard warfare. Indeed, even twenty years after that war, a large number of Vietnam veterans still carried their wounds around, wandering in the streets, far away from any sort of homecoming. They lived on the margins of society, constantly suffered shortages of food and clothing, and were suspected of undesirable behavior and activities normally attributed to drug addicts and petty criminals. All this pushed them into an abyss of despair where loss of faith and self-respect loomed large. In short, the majority of them were forgotten veterans. Was it because they had not emerged from a war that was won with glory by their side but instead from the first war the U.S. ever lost… they sacrificed a youthful portion of their lives, and endured personal losses in the service of the richest country in the world, only to face the crude reality after being discharged that a small number of them had to live as homeless people on pavements of city streets, live in need of basic necessities and in lonely and desperate states of mind… having stepped out of Vietnam battlefields [they] never reach home. (In Retrospect, pp. 371-372)

[they] never reach home … Living in exile on their own motherland, like protagonist Phan who after 17 years was still being constantly haunted by the war in his mind… Could not discount the “bloodless wounds” pertaining to PTSD – post traumatic stress disorder. Ah! The Vietnam War personified in the scene of Gumber, an American soldier, hanging himself on a beam at a bus stop, his soul finally at peace: No more Vietnam. Vietnam never again. The Vietnam War and the pain of all war wounds truly ceased to exist. Only at this point did he actually say farewell to Vietnam… And Gumber would not be the last Vietnam veteran to die from the Vietnam war (In Retrospect, pp. 377, 378). Then, there was that ARVN medical corpsman, who was not wounded during the fighting but by… an anti-personnel mine laid in his field by some unknown person at an unknown time… Peace had returned and Tung had contemplated an enduring happiness, but as things turned out, he would be able to do little more than manage his days one at a time… (A Former ARVN Medical Corpsman, pp. 392, 393)

I had, like the author, asked myself what wall, what history book would eventually record all those post-war deaths and wounded?

WHEN THE LIVING FORGET ABOUT THE DEAD,

THE DEAD DIE A SECOND TIME … (The Promise of a Glorious Autumn, p. 397)

I imagine myself standing and watching the flag fluttering in the blue sky during a ceremony commemorating the souls of the departed soldiers coming back from the dust, hills, rivers, streams, jungles of past fighting and the joy of mystical reunion that will finally free me from the melancholy that has obsessed me for so long.

Not counting those who died, among the present survivors are a few truly worthy to be called heroes because of their legendary feats of arms. (The Battle of Saigon, p. 266)

… How many pages of a book would be needed to recount outstanding feats of arms performed by the nameless heroes engaged in this operation on Cambodian land? The 81st Recon Team’s activities for the duration of 96 hours, from the moment their feet were on the ground, could be viewed as the unfolding of a splendid epic. (Buddha’s Tears, pp. 287-288)

… Many years had passed since that dark day, during which time the vicissitudes of life were too many to count and too tragic to forget. While Phan was in a communist re-education prison camp, the remembered image that most came to mind was never a great military parade in full colors and uproarious sounds on Armed Forces Day of pre-75 South Vietnam. Instead, the ingrained memory enfolded the quiet marching footsteps of an unknown squad during the last hours of the city of Saigon, before it lost its name. No one knew the whereabouts of that warrant officer - in what re-education camp, alive or dead; nor was known the fate of those courageous common soldiers who upheld military discipline until the last moment. Are there a few lines in some unfinished military history dedicated to the extraordinary march of that lowly group of military personnel, which embodied the magnanimity of the armed forces in the last hours before the whole army disintegrated? (No Farewells to San Francisco, pp. 353-354)

The question is really poignant, some kind of fatigue, despair has set in… Where is that true history that would render justice to the soldiers so that they can rest with their fellowmen’s true gratitude, remembrance, not in an abandoned forlorn cemetery with fallen leaves covering broken tombstones and empty incense burners. In any case, now, we have Ngo The Vinh’s work to serve as a deserving commemoration …

… Like the majority of Vietnam veterans, Jim was considered alive, but they were like scattered fragments of bombs and artillery shells that had not actually left the battlefields of Vietnam. Would there ever be another commemorative wall in Washington, a wall long enough to have all their names carved upon it and thus honored? (Another Wall, p. 368)

A second wall needs to be built, additional pages need to be added to the military history book… Probably it would take a long time, may be forever, for those wishes to be fulfilled… However, those wishes are like a message full of compassion the author wishes to send out.

NGO THE VINH, A SOCIAL ACTIVIST

In “The Battle of Saigon”, in the face of corruption and injustice, the author voiced a concern:

… Beside the murderous battlefield familiar to them, they must confront another frontline, a barricade more depressingly wearisome: the corruption and injustice people are being forced to bear in sorrow and shame. For thirty years now, there have been many heroes in war, while social activists have proved to be few and far between… (The Battle of Saigon, p. 275)

Ngo The Vinh is a fighter at the frontline, a medical doctor, an author, and a journalist. With all those attributes, the books he wrote and the things he did, Ngo The Vinh is truly a social activist, a deserving hero. If he lacks in courage, in his idealist commitment to work for others, he would not have ventured into the social battlefront like working for the magazine Tình Thương during his student years at the Medical School to propagate medical ethics and love of humanity. For a long time, he risked his life at the battlefields, his heart beat along with the drum beats of war gaining the precious experience that helped him write books like The Battle of Saigon. Thank to Providence, his life was spared during the fighting so that he could do the research and write about the death of a river. At great risks, he traveled to the source of the Mekong River to later write several valuable books about it. He dealt with issues pertaining to the people’s life and sounded the alarm about all devastating threats in order to contribute to the preservation of the environment in view of building a better, more equitable, more humane society. Aren’t those within the purview of a social activist? What gives him the energy to accomplish all that? Probably all these things: enthusiasm, passion, compassion and an unrelenting dream as well. And he has consecrated his entire life to his ideal profusely, enthusiastically.

... “Such stories taking place no less than half a century ago in a place which now seems so sorrowfully distant all of a sudden resurged in a lingering way in the memories as well as in the hearts of each of us once we have the “Battle of Saigon” at the night table”. (Hoang Ngoc Nguyen, In Search of Peace With “The Battle of Saigon”, p. 508)

It must be so because even though I have finished reading it, I still feel I am not done with it. I had to leave it on the small table on which stands a lamp that emits a warm soft light so that I can look at it, look at it every day at the wounds that had not really healed. Look, until the day I could transform them. And the key to that transformation is to be able to witness the realization of dreams – at least those of Ngo The Vinh – of those who share the same tragic past and eagerly nourish beautiful dreams, one of those is a warm sweet home for “A Hundred Children, A Hundred Clans” – Vietnamese descending from the mythological union of the fairy Au Co and the Dragon King Lac Long Quan. This home base would be a location where values of the past were collected and stored, a gathering place where the ebullient spirit of life in the present was demonstrated, and a starting point from which to challenge the course of future. It was to be, above all, a pilgrimage destination for every Vietnamese no matter where in the world he or she lived.

And … Realization of any dream did not depend solely on the brave heart of one person; it had to be based on the will of a collective whole that together looked in one direction, together cherished and longed for the joy of a fulfilled dream... (A Small Dream for The Year 2000, p. 436)

I would like to use the words of Tim Page to conclude:

[Reading the Battle of Saigon] the whole time you hear the plaintive tones of a man attached still to the spiritual roots of that haunting country Vietnam. (TIM PAGE, Life – Time, UPI Freelance Reporter)

NGUYEN THI KHANH MINH

Santa Ana, October 6, 2020

* the words used by Ngo The Vinh in the short story In Retrospect.

** The bilingual collection of short stories “The Battle of Saigon” was published and sold on Amazon since 10/16/2020.

Nguyen Thi Khanh Minh was born in Hanoi, her hometown is Nha Trang. She graduated with a BA in Law in December 1974, the last class of the Saigon Law School. Her works in poetry and prose have been published in Vietnam and the U.S. during the years 1991- 2020. She is now living in Santa Ana, California, U.S.A.